UBC Psychology’s Motivated Cognition Lab

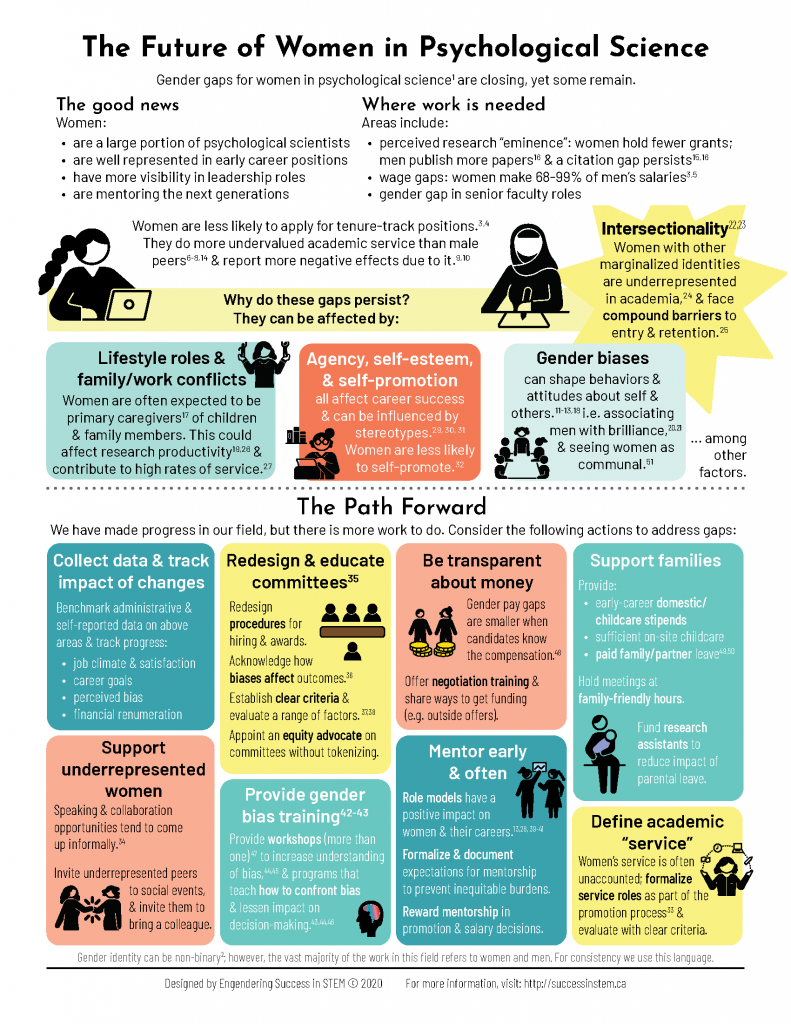

The first gender parity review of psychological science shows women outnumber men at the undergraduate, graduate and assistant professorship levels—but they remain under represented at senior faculty levels, are paid less, publish less, and receive less recognition than men at equivalent levels.

Dr. Toni Schmader, a professor in UBC’s department of psychology, is one of 59 authors who published a comprehensive review on women in psychological science. The publication, The Future of Women in Psychological Science, explores the status of women in the field in ten distinct areas with a goal of identifying where gender gaps exist—and why those gaps exist.

Toni Schmader

Dr. Schmader, who is director of the Engendering Success in STEM Consortium, examines how people are affected by various social identities, stereotypes, and biases.

She joins us for a Q and A to discuss this research, why gender gaps exist, what psychology is doing well, and how we can narrow the gender gap.

Tell us about this body of research. What has this analysis shown?

Psychology has made important strides with regards to gender parity in the last few decades. Women now outnumber men in undergraduate and graduate training and are as likely to receive assistant professor positions, grants, and promotion—when they apply—as are men. Yet these positive data points exist alongside remaining disparities: Women are less likely than men to apply for Assistant Professorships and grants, and are both less likely to publish and to get cited for their work. Women remain underrepresented at senior faculty levels, are paid less than men at equivalent levels, and are less eminent in the field and on the world stage.

Why do gender gaps persist in psychological science, despite the large proportion of women in the field?

Several factors can play a role in contributing to or maintaining the disparities that remain. Structural factors related to gendered caregiving roles put women at a disadvantage professionally. In their professional networks, women still face some forms of bias as researchers, teachers, and colleagues. These biases might lead women to be cited less for their work, invited less to be elite conference/colloquium speakers, and sought out more for service positions.

Stereotypes about competitiveness, self-promotion, and who “counts” as a brilliant scientist may even affect women’s self-perceptions and behavior. This might play a role in why some women do not apply for tenure track positions, seek to published in the highest profile outlets, apply for top grants, or position themselves as public intellectuals. Together, the disparities that do exist might contribute to differences in productivity that seem to justify differences in men’s and women’s stature in the field.

What is psychological science doing well, in terms of gender equality?

Like many sciences, Psychology historically had inequitable gender representation. In some areas, Psychology has now turned this around.

- Women now receive PhDs and are being hired as Assistant Professors at a historically high rate

- When women apply for Assistant Professor positions, they are sometimes more likely to get them than equally qualified men

- Women are also as likely to get promoted and tenured as men

- When women apply for grants, they are equally as likely as men to get them; in some cases (e.g., mentored awards), they are more likely than men to get them

- There is roughly equivalent financial parity at the Assistant Professor stage

How can psychology create change for women in the broader academic community and beyond?

An awareness of how far we’ve come–and how much further we have to go–is necessary to chart a path forward for future women psychologists. We suggest a path forward and hope others agree with the editor that this review is essential reading for policy makers, university administrators, department chairs, and anyone who wants to pursue a scientific career. Here are few concrete examples:

- Universities and departments can support parental leave policies for women at all stages (including graduate school)

- Departments can make efforts to equalize service assignments to ensure gender equity in workload

- Mentorship programs can help to foster inclusion and belonging, which might be especially important for women with intersectional identities

- Ensure that the department/university has effective anti-bullying and anti-harassment policies in place