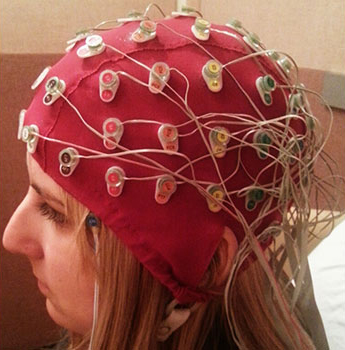

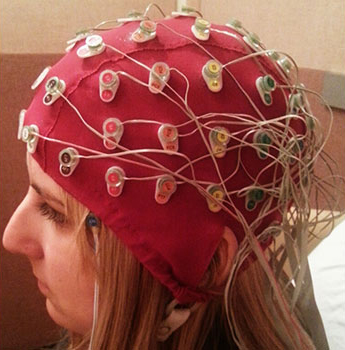

Photo credit: Julia Kam

UBC research shows that chemotherapy can lead to excessive mind wandering and an inability to concentrate. Dubbed ‘chemo-brain,’ the negative cognitive effects of the cancer treatment have long been suspected, but the UBC study is the first to explain why patients have difficulty paying attention.

Breast cancer survivors were asked to complete a set of tasks while researchers in the Departments of Psychology and Physical Therapy monitored their brain activity. What they found is that the minds of people with chemo-brain lack the ability for sustained focused thought.

“A healthy brain spends some time wandering and some time engaged,” said Todd Handy, a professor of psychology at UBC. “We found that chemo brain is a chronically wandering brain, they’re essentially stuck in a shut out mode.”

Handy explains that healthy brains function in a cyclic way. People can focus on a task and be completely engaged for a few seconds and then will let their mind wander a bit.

The research team that included former PhD student Julia Kam, the first author of the study, found that chemo brains tend to stay in that disengaged state. To make matters worse, even when women thought they were focusing on a task, the measurements indicated that a large part of their brain was turned off and their mind was wandering.

The researchers also found evidence that these women were more focused on their inner world. When the women were not performing a task and simply asked to relax, their brain was more active compared to healthy women.

Kristin Campbell, an associate professor in the Department of Physical Therapy and leader of the research team, says these findings could help health care providers measure the effects of chemotherapy on the brain.

“Physicians now recognize that the effects of cancer treatment persist long after its over and these effects can really impact a person’s life,” said Campbell.

Tests developed for other cognitive disorders like brain injury or Alzheimer’s have proven ineffective for measuring chemo brain. Cancer survivors tend to be able to complete these tests but then struggle to cope at work or in social situations because they find they are forgetful.

“These findings could offer a new way to test for chemo brain in patients and to monitor if they are getting better over time,” said Campbell, who also conducts research to measure how exercise can improve cognitive function for women experiencing chemo brain.

This study was recently published in the journal Clinical Neurophysiology and received funding from the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation BC/Yukon.

This media release was originally published on the UBC News website.