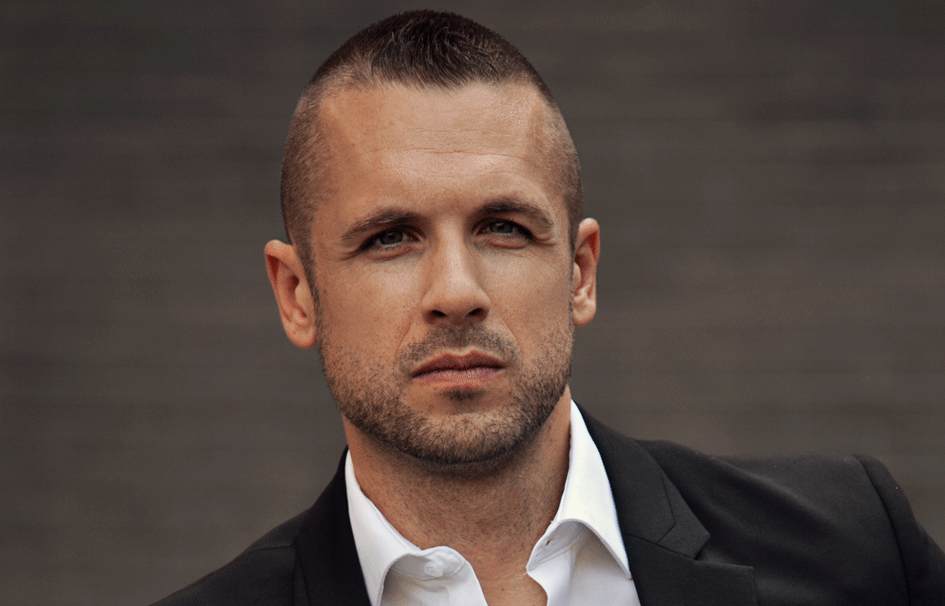

UBC Psychology Sessional Instructor David King

Dr. David King’s diverse teaching experience at the university level spans courses in research methods, health, gender, abnormal, personality, and social psychology. His goal is to stimulate intellectual curiosity and develop critical thinking in students.

Fourth-year Psychology major Stella Domnich sat down with King to get his ideas on teaching and beyond. In this interview, King shares his tips for struggling students, his experience as an undergraduate student, his favourite campus locations, and the research projects he’s excited about.

As an instructor, what is something you see in students that you wish they could also see? In other words, what is something you see in us that you don’t think we recognize?

One thing that I try to get across to students, and that I try to be explicit about, is that I really wish they would think beyond exams and grades. I understand that grades are important for obvious reasons; they’re a major determining factor in undergraduate success, and I get that. But I think having an eye for the real value of what you’re learning is so critical because what you take away from the course in the long run is ultimately the most helpful. Applying what you learn in a real way makes you a more effective learner, but this is something that is difficult to capture with exams. It doesn’t translate well. At the very least, I wish students would look beyond their grades and try to see the bigger picture. The entire learning experience will feel more valuable.

What is a good resource for students who are struggling in your class?

I think the biggest thing is to use the TA and instructor office hours. That may sound too obvious, but in my seven or eight years of being a TA, and now two years of teaching, I’ve been surprised by how little students make use of office hours. Before seeking out other resources or services on campus, which are often less convenient, students should use us. Use your front line connections to the course because that’s where the best help is; we’re the experts on that particular course, so start with us. Any external resources will not have a good handle on the course itself (especially not the content), so they’re always limited in that regard. This past term is a good example. I had almost 400 students across classes, but I managed quite easily with the same number of office hours I’d normally hold for only 200 students. Why? Because I just didn’t need more than that. The students didn’t come.

Do you have a favourite spot on campus?

I would say that I love being anywhere on campus, as long as I’m outside (and there isn’t construction close by). I love the campus itself, and being outside. I’ve gone to the Rose Garden a number of times to sit, but it’s hard to name one specific location as my favourite. I also like going to Wreck Beach when no one else is there. I don’t go there nude (uncomfortable laughter follows), but it’s probably one of the nicer beaches in Vancouver.

What’s one thing you know now that you wish you knew when you were an undergraduate student?

This is such a hard question. It’s tough because there are a lot of things I wish I had known; many I think I did know at the time, but just didn’t get entirely, or fully grasp. One thing I wish I had figured out earlier is knowing when to take advice; knowing when to take it and knowing when to pass on advice altogether. The reason I say this is because sometimes, and I guess you see this more and more as you progress through your education and your career, you find that you start getting conflicting advice. Advice is so important to the whole process, so I don’t want to suggest that it should be ignored. You desperately need advice because there are a lot of things you don’t have easy access to. This is especially true as an undergrad, in terms of information about how grad school works, etc., but there’s always a point where the advice starts to conflict and become unclear (perhaps due to personal agendas, emotional investment, politics, whatever). In those situations, the best thing is to do is what’s right for you. You eventually have to say to yourself, ‘Okay, this is what’s right for me, even if it makes someone angry or someone’s not impressed by my decision.’ In the majority of the decisions we’re faced with in life, there’s no one right way; there’s rarely only one path to take. So you have to consider what your gut is telling you. I feel like I’ve always known this on some level, but the extent to which advice can be conflicting is surprising. It’s kind of like the whole “go follow your heart” thing, but it doesn’t have to be that cliché.

What is one person, place, or thing you could not live without?

So I recently had someone ask me to rate the importance of music in my life on a scale of 1 to 5. I instinctively said 5, without thinking about it at all, and I was quite confident that I was a 5 on this scale. No one else in the group who was asked said over a 3. Now I’m not a person who is musically inclined – I don’t play an instrument, I think I’m tone deaf when it comes to singing, but I was really surprised to recognize how important music is in my life. It can really help you get through things, and I think it’s a big one. If anything, music can serve as an easy and simple connection to something more than just our day-to-day. It allows us to get under the surface, or above it all somehow. I can’t imagine not having the opportunity to listen to music on my way to work, or while I’m working, or while I’m falling asleep at night.

Can you tell us about any new research in the field of health psychology that you’re excited about?

There are two big things I’m involved in right now. One is a project that we’re just starting up at SFU as a part of my post-doc. We’re looking at the daily relationship dynamics of older gay couples who have been together for a long time. The reason I’m excited about this is that it’s an area of research that is still largely unexplored. A lot of my past work has been in the area of relationships and couples, but so much of that literature has consistently focused on heterosexual couples – often who are married in the traditional sense of the word – and, you know, that’s changed, and it’s still changing. This project should really help elucidate a lot of questions that remain. For example, there are a lot of assumptions being made about what those relationships look like and how they’re different from heterosexual relationships. The other project is one that I’m working on with Dr. Anita DeLongis (my PhD supervisor) at UBC, and it looks at how people respond to disease threat when there’s an outbreak. One of the things we want to do right now is go into the field and understand why people perceive Ebola and other exotic diseases as high-risk in North America even when there isn’t much of a risk at all. It’s an interesting question to ask, why people might perceive greater threat from Ebola when they’re more likely to die of the flu or cancer or heart disease – and they’re not seeing those things as threatening in comparison. It’s part of a longer line of work on disease threat that I feel really fortunate to be involved in.

David King is also a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Simon Fraser University and a writer and blogger. You can read more about his thoughts and philosophies on life on his blog www.davidbothered.com.