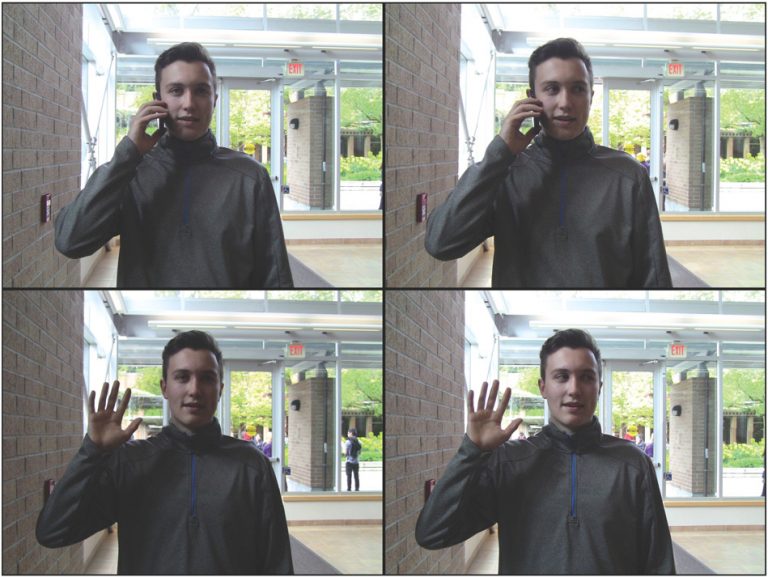

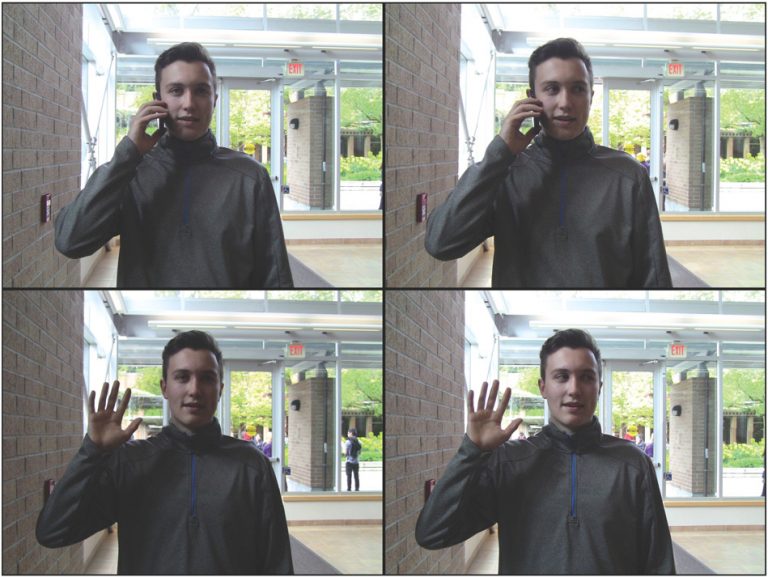

Illustrative confederate actions. Final hand positions for the conditions in which the confederate raised his hand to answer a phone (top) or wave (bottom), with eyes positioned

either straight ahead (left) or tracking the passing pedestrians (right)

New research out of the Department of Psychology is the first to show that covert attention, such as paying attention out of the corner of your eye, is critical to guiding appropriate looking behaviour when we’re around other people.

The paper “Camouflaged attention: Covert attention is critical to social communication in natural settings” was published in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior. The research, conducted in the Brain and Attention Research (BAR) Lab, explores how people use visual attention in everyday social settings.

Kaitlin Laidlaw, a 2016 PhD graduate and BAR Lab member, is the study’s lead author and the co-authors include Dr. Alan Kingstone, Director of the BAR Lab and Professor in the Department of Psychology at UBC, and Austin Rothwell, a Research Assistant in the BAR Lab.

Kaitlin Laidlaw

This paper was one of several studies that were included in Laidlaw’s PhD thesis, which received this year’s Belkin Prize for best PhD dissertation. We spoke with Laidlaw about this new research, the different disciplines it touches on, and her follow-up research.

First all, what do we know about people using eye movements to communicate in social settings?

Most people understand that our looking behaviour conveys a lot of information to those around us. You might look to your boss while they are speaking in order to signal your attentiveness, or a child might look to their caregiver to gauge their reaction when they spill their drink. Similarly, if in the middle of a conversation your friend suddenly looks away, you might find that you follow their gaze without even thinking about it. Many of these behaviours have been well studied in the laboratory, usually by recording eye movements while individuals are shown images or videos of other people. Although we can easily think of many ways in which we use our own and other people’s gaze in everyday life, there is surprisingly little research exploring whether the principles of social attention that have developed within the laboratory translate to predict and describe real world behaviours.

What was the purpose of this research?

This study is one of only a handful of real-world studies looking at how people attend and look at other people in social situations. Laboratory tasks examining how people pay attention to social scenes often find that we prefer to look at other people, and in some cases find that we cannot help but look at social stimuli (e.g. faces, eyes). Based on these results, it might be predicted that we would also show a strong bias to look to other people in everyday social settings. However, looking at a picture of a person is a very different experience than looking at a person face-to-face, precisely because in the latter case, our gaze can communicate information to the person looking back at us. In fact, other research from the BAR lab has demonstrated that people do not look to other people in real life nearly as much as when the same person is presented on video.

Does this mean that lab tasks are incorrect in concluding that people attend to others? Not necessarily. Looking isn’t the only way we pay attention. It’s also possible to pay attention without looking – think about when you pay attention to something ‘out of the corner of your eye’. This is known as covert attention. Although people may not communicate their attention to strangers in social settings, we wanted to see whether they are still ‘silently’ attending to those around them using covert mechanisms.

Can you describe your methods for observing the behaviour?

Example camera angles from the outside (top) and indoor (bottom) locations. Confederate is grey shaded figure, approaching pedestrians are represented as white shaded figures.

To test whether people covertly attend to others in an everyday social environment, we filmed pedestrians walking in public spaces on campus. It is challenging to measure covert attention, because by definition, it does not elicit an easily observable behavioural change like an eye movement. However, we know that covert attention allows us to discriminate details better. We reasoned that if a pedestrian were able to discriminate a subtle action performed by another person without looking, then we could conclude that they had directed their covert attention to that person. To do this, we measured reactions to subtly different actions performed by an undergraduate actor. The actor stood in a well-travelled pedestrian pathway while the experimenter sat with a video recorder some distance back. When a pedestrian approached, the actor would raise his hand and say ‘Hey’, either while holding a cellphone phone to his ear or while holding his hand up in a type of still wave. For some pedestrians, he also followed the pedestrian with his eyes as they passed, while for others he avoided making eye contact and stared straight ahead. The differences between conditions were subtle, but if you were paying attention, easy to discriminate. This was exactly the point.

For pedestrians who were not looking at the actor to begin with, we then tallied how many people looked up following his action. Someone waving signals an invitation to interact, to which a socially appropriate response would be to acknowledge the greeting in some way (e.g. by looking, by returning the wave, etc). In contrast, answering a phone is a private action, to which we expected pedestrians would avert their gaze (it’s rude to stare, after all!). Crucially, only if pedestrians were covertly attending to the actor would we expect to observe this division of reactions across conditions. Otherwise, pedestrian responses would not differ based on the actions performed. Over the course of a couple of months, we collected and tallied the looking responses of over 300 pedestrians.

What was the main finding of the study?

Even though pedestrians were not looking at the actor, reactions to the actions were very different! Pedestrians were over five times more likely to look up at the actor after he waved (about 68% of pedestrians look) than after he answered his phone (29% look). In fact, people were not significantly more likely to look at the actor answering his phone as compared to when he did nothing at all. We didn’t find any difference in looking responses based on whether the actor looked at the pedestrian as they passed or if he stared straight ahead. This tells us that even though pedestrians did not look at the actor, they were still covertly attending to him. We suggest that this type of ‘quiet’ attentional focus can help people discriminate other’s actions so that they can better decide when it is appropriate to look or not. In this way, covert attention allows us to gather social information without signalling to others that we are doing so, while also maintaining the communicative value of looking.

Is there anything in this research that surprised and excited you?

At first pass, it may come as a surprise that pedestrians were no more likely to look at the confederate when he stared at them as compared to when he did not. After all, aren’t we especially sensitive to the gaze of other people? Interestingly, the studies that often report gaze preferences have measured behaviours at much closer distances, where the observer is already looking directly at, or very close to, the eyes of the other person. It seems reasonable that when someone is further away, larger changes like a wave would be more likely to elicit a reaction than a small change in gaze.

Can you touch on the different disciplines that this research crosses?

These findings are relevant to cognitive and social psychologists, but also to sociologists and evolutionary biologists. Though nonhuman primates do have the ability to covertly attend, the all-over dark colouring of their eye more naturally camouflages their gaze direction. In humans, however, our eyes are made to communicate: the high contrast between the dark pupil and the light sclera serves to attract attention, even when we may not want that attention. Though it remains to be tested, it stands to reason that covert attention may play a greater role in human social interaction than it does in other nonhuman primate species.

Has this research influenced your subsequent work? Do you plan any follow-up studies?

Absolutely! There is a history in psychology of testing people in isolation. There is a lot that can be learned this way, but so much of our everyday experiences are social. It is becoming very clear that we need to consider how other people influence even the most basic cognitive processes. We’re always coming up with new ways to investigate social attention in more relatable, but still meaningful ways.

You received your PhD from UBC on May 27, 1016. What are your plans after graduating?

In January, I started a postdoctoral fellowship at Western University’s Brain and Mind Institute, working with Drs. Jody Culham and Melvyn Goodale. I’ll be extending my research into social attention to explore how other people influence action planning and will also explore the neural mechanisms related to social attention and action.

Related

- New research on eye-tracking devices sheds light on the implications of wearable technologies

- BAR Lab research a feature story in UBC’s 2013/14 Annual Report