Photo source: COP26

The 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) takes place from October 31 to November 12 2021 and one of its four goals is to help countries adapt to climate change in order to protect communities and natural habitats.

From creating disaster preparedness apps to training local climate champions, researchers—including UBC Psychology Associate Professor Dr. Jiaying Zhao—are already working with communities to help them prepare for the effects of climate change.

Read more about the work Dr. Zhao and other UBC researchers are doing.

When it comes to climate action on mitigation and adaptation, we need everyone involved, says Dr. Jiaying Zhao, Canada Research Chair in Behavioral Sustainability and associate professor at IRES and the department of psychology in the faculty of arts.

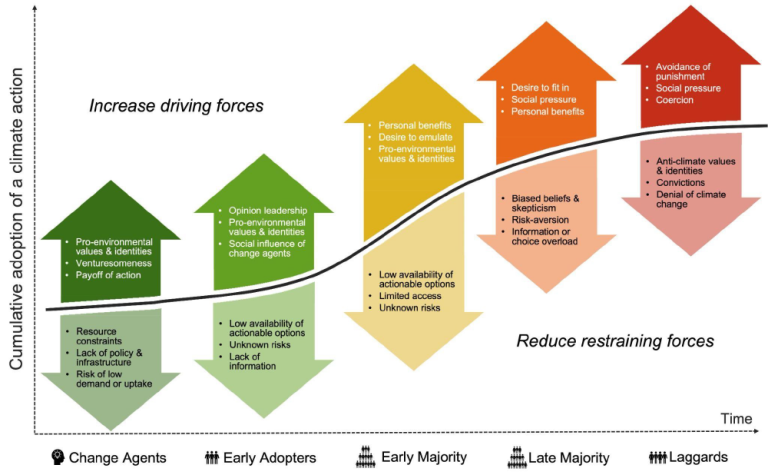

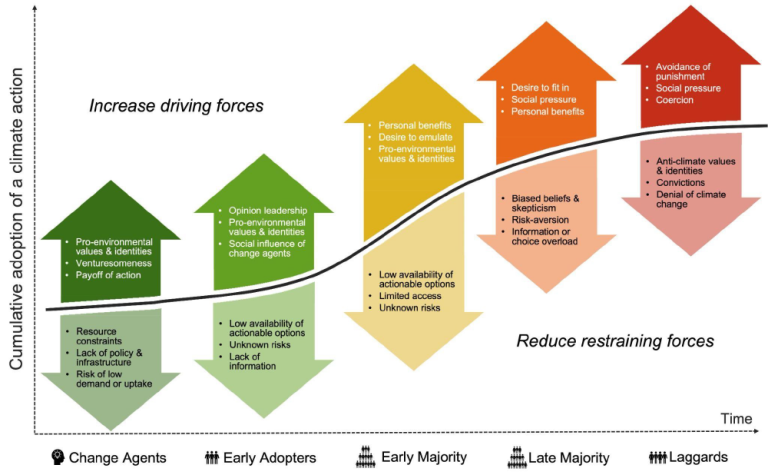

She and her colleagues have posited a set of interventions to target different subsets of the entire population to make sure no one is left behind.

Two of these five groups, the “late majority” and the “laggards”, make up 50 per cent of the population and are often overlooked by behaviour change interventions, the authors say.

The “late majority” are characterized as adopting climate actions to fit in with others. Interventions include using social norms, peer pressure, and peer influence to encourage climate action. The “laggards”, or those most reluctant to act, need peer role models to deliver messages and to endorse climate action, says Dr. Zhao. “You need to use the right messenger to deliver the right message.”

Policy makers and researchers should acknowledge these different groups of people and their distinct motivations for climate action, and tailor interventions to each group, she says. “We should get everyone on board, not just the keeners, as soon as possible.”

Planning for a disaster can be scary, but UBC researchers are making it easier with a new app tailored to individual households.

Dr. Ryan Reynolds, a postdoctoral researcher in the faculty of applied science’s school of community and regional planning, found residents in Port Alberni were confused as to which households were at risk and where to find information following a tsunami warning and evacuation in 2018.

Hoping to address this gap, his team has created the Canadian Hazards Emergency Response and Preparedness Mobile App (CHERP) app, which will be piloted in seven communities on Vancouver Island starting next month. “I know from speaking with people post-disaster that anything we can do to reduce that confusion goes a long way to building trust in emergency responses.”

The app helps residents create preparedness, communication, evacuation and on-the-day emergency response plans for local hazards and potential disasters such as sea level rise or coastal flooding. Not sure if your household is in the inundation zone for a tsunami warning? The app will tell you based on your location.

A thorough list of inputs helps individualize plans for each household, including whether someone menstruates, has anxiety, accessibility issues, is part of the LGBTQ+ community, signs, is a refugee or in Canada on a temporary visa. And pets aren’t forgotten: users can input the number of animals in their household.

Preparing for emergencies is like insurance, says Dr. Reynolds. “You do a little bit of work now and hopefully reap the benefits down the road. We know things like sea level rise, coastal flooding, tsunamis, are going to happen and we can put steps in place to prepare.”

Tackling climate change over wine and cheese with your neighbours sounds too good to be true. But Dr. Stephen Sheppard, a professor emeritus in the department of forest resources management in the faculty of forestry, says local climate change action should be fun. “If you can get people to do things together, you get safer, more resilient neighbourhoods but also stronger communities. You could go to the pub, have some fun with it – it’s got to be fun, or no one will do it.”

Over the next 12 months, his team will train local residents for Cool ‘Hood Champs, a free program hosted by four Vancouver community centres. In a series of three workshops, participants learn to identify local climate targets, impacts and solutions, and craft their own climate action plans with practical actions, ranging from installing a shade structure or a vegetable garden to watering neighbourhood trees during a drought.

This year’s program is an extension of a pilot from last year, where 29 participants completed all the workshops, and 70 per cent chose to take home trees to plant in their yards. Local action is vital, says Dr. Sheppard, because individual behavioural decisions affect whether governments achieve emissions targets, and practical solutions can help people feel better. “What can you do about climate change? You can ignore it, worry about it, or do something about it, using positive processes you can control.’

Dr. Sheppard and his team are also piloting a three-year program with Oak Bay council, where citizen workshops will be hosted through community hubs including schools, churches, and volunteer programs, with funding and staff support. “The pilot will show with backing and funding, citizens themselves can run workshops, take local action and involve others, sustainably.”

However, climate adaptation interventions are not automatically positive, says Dr. Sameer Shah (he/him), a sessional lecturer at the UBC Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability (IRES) in the faculty of science. When applied without consideration of the social context, they can deepen inequities.

In a study published in June, Dr. Shah and colleagues looked into the Government of Maharashtra’s campaign in India to make 25,000 villages drought-free by 2019, a campaign that cost nearly US$1.3 billion.

The team interviewed households in three villages, as well as government officials and key informants, and found that government interests had led to a narrow focus on certain types of water conservation interventions. These benefited a particular group of people, generally those who were already well-off, and often excluded those who didn’t have enough land or money to invest in water-related adaptations, or were located further away from waterbodies, including members of historically disadvantaged groups.

According to a 2020 report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India, the campaign had little impact in achieving water neutrality and increasing groundwater level. Here, technical solutions are not enough, says Dr. Shah, and interventions need to incorporate the social context in which they occur. “As researchers, we can’t just say ‘this is the science’ for an intervention, and then hang up our hats. We need to be focused on issues of governance and distribution.”

This story was originally featured on the UBC News website.